Dear readers,

I hope all is well with you. Over the course of writing this paper, I have had many reflections and achieved new milestones. This paper marks my first attempt at exploring a new style of writing and research, as well as delving into the world of emerging markets. I feel proud but, at the same time, hesitant to think that the progress I have made is a reflection of real growth rather than just luck. Nonetheless, I remember the advice given to me by my first mentor who taught me about investing and life: "Part of being a good investor is the ability to be comfortable with uncertainty." I should, therefore, strive to live up to this advice.

Skip to page 2 for the investment paper. The following are my thoughts for personal journaling.

A core teaching of Warren Buffett's investment philosophy is the simple idea of buying great companies at reasonable prices. Additional nuances include concepts such as a high degree of certainty, which is achieved when a subject is within one's circle of competency, as well as business fundamentals like high barriers to entry, the ability to reinvest at a high return on capital, and competitive advantages to protect such moats. Evaluating these fundamentals refers to the "art" of analysis, although much discretion may also be exercised in the valuation segment of the analysis process. As a student of economics, I have always wondered how I could incorporate the countless pages of academic literature on economics and theories into investing.

Over my (albeit short) investing journey, it seems that economic theories often do not align well with pragmatic investing. Much discussion has already been made on this topic, which suggests in short that a static and controlled theory (economics) cannot be applied dynamically (investing) while expecting the same level of success and outcomes. More often than not, we should strive to find companies that can excel regardless of the macroenvironment.

But as I was analyzing the next company I will be deep-diving into, I realized some specific areas of economic habits, especially in the case of analyzing demographics and population characteristics, helped provide me with more perspective on the business itself beyond the usual business fundamentals. This is what I argue gave me a unique perspective on identifying the key moat in the business. I hope you will enjoy and learn a bit about Poland and specifically, Dino Polska, as much as I have enjoyed writing this.

Cheers,

Ryan A.

Initial Thoughts on Dino Polska

When I was screening for high ROIC businesses in the global consumer space, some names that stood out included companies like BIMAS, which I previously covered. However, from a purely quantitative perspective, Dino Polska is one of the best-performing companies out there. Personally, I felt that BIMAS had a better competitive positioning, given its majority market share, which is about twice that of its closest competitor. In the consumer staples space, such a significant gap in market share serves as an extremely strong moat.

On the other hand, Dino Polska is one of the rapidly growing companies aiming to challenge the BIMAS equivalent of Poland, Jeronimo Martins, the operator of Biedronka-branded stores across Poland. Now, Dino Polska is by no means cheap. It trades at around 30x PER or 25x NTM PER. For a grocery chain operating in a price-competitive market, this is certainly something to take note of. At best, it could only be considered a "Growth-at-a-Reasonable-Price" (GARP) stock.

However, what caught my eye is that Dino performs much better than its competitors from a financial perspective. It offers close to twice the number of SKUs and product offerings compared to discounters like Aldi and Biedronka. It boasts a fully operational fresh meat butchery in every store, while discounters like Aldi and Biedronka only offer packaged meats. Yet, all things considered, its margins are approximately 2x higher than those of Aldi and Jeronimo Martins (the owner of Biedronka). This made me wonder, in the event that companies like Aldi and Biedronka start expanding their portfolio of SKUs and offering fresh meats, could the margin gap widen not just to twice but three times greater?

Therefore, what I am curious about in this paper is, firstly, to understand the dynamics and relationship between incumbents and entrants in the consumer staples sector. I want to find out what exactly Dino Polska is doing right to offer a much more value-adding experience for consumers without compromising its financial performance. Then perhaps, this understanding may justify the valuation multiple for Dino and warrant a closer look at it as an investment opportunity.

A Quick Look into Poland’s Macroeconomics and Demographics.

Poland is a country on the eastern bloc of the European continent. It has 16 main voivodeships (provinces) with a total population of 38 million in 2021. Its capital is the renowned Warsaw, famous for all things Chopin and its grand palaces. The country has a GDP of USD689 billion in 2022, up from USD 142bil in 1995. Poland achieves an reasonably high growth rate of 4% since 1995 and has become the 5th largest economy in Europe, by GDP (PPP adjusted). However, when compared against the standard of living with the average American, the average Pole’s standard of living is about half that of an American. Therefore, most poles engage in little discretionary spending and are price conscious when shopping for consumer goods, including groceries.

As a country, Poland offers universal free public healthcare and education (including tertiary), extensive provisions of free public childcare and parental leave. Poland was one of the bright spots in Europe, often noted as a “happy” country to stay in, with ratings (albeit subjective) close to Finland and above the European average. Population sentiments about the future were ranked the highest in 2018 among advanced economies, with 64% of population thinking that their children will be better off in the future. Afterall, with the country experiencing its highest growth in decades, everything seems good. That is until the triple whammy, economic, black swans, cocktail mix of the COVID19 pandemic, outbreak of war between Ukraine and Russia, and unprecedented inflation numbers. The COVID19 pandemic put a paused in Poland’s economic growth, slowing its 12% GDP growth in 2019 and 2020 to 1% in 2019 and 2020 although a recovery of 13% was experienced in 2021. But, with the war, the growth has slowed back down to 1%. Furthermore, with record high gas prices (appendix), inflation reached 14 % in 2022, highest levels since 1997. Nonetheless, I believe Dino Polska, given its positioning as a proximity supermarket and discounter, would mean that it would benefit from higher gas prices and inflation, as customers would opt to walk to their stores and trade down from supermarkets.

Demographic and Consumer Analysis

Firstly, it's important to note that in Poland, 60% of the population resides outside of large cities. This is in contrast to other emerging countries like Turkey and the Czech Republic, where only 20-25% of the population lives in rural areas. Even if we narrow the definition of "rural," Poland still has around 40% of its population living in rural segments, which is twice that of other European nations like Germany and France. This means that companies need to have a rural penetration strategy, as purely focusing on urban areas may not be an effective strategy, given that grocery spending does not vary significantly between urban and rural areas.

Secondly, meat consumption remains a significant staple in the Polish diet. Despite trends of declining meat consumption per capita due to the onset of vegan alternatives and dietary changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, the annual meat consumption of Poles still stands above the EU average of 69 kg annually, at 76 kg annually.

Thirdly, there has been a shift in consumer purchasing habits and perceptions across different grocery distribution channels. According to a paper published by the University of Lublin (source in the appendix), consumers in Poland used to perceive buying groceries at discount stores as a sign of low social status. However, this perception is changing, and it is now becoming fashionable. 63% of respondents state that they prefer to purchase food products primarily in discount stores, while only 16% of respondents prefer supermarkets and hypermarkets as their primary shopping channel. However, it appears that this trend is mainly exclusive to food products and not transferable to other products such as apparel and cleaning products, where supermarkets remain the preferred channel. Based on my investigation, one of the key reasons for this is convenience and the freshness of products. Discount stores are typically much closer to customers compared to larger-format channels like hypermarkets and supermarkets. Furthermore, discount stores are more likely to refresh their inventories on a daily basis, as compared to the less frequent refreshment of inventories in supermarkets and hypermarkets.

While COVID-19 accelerated this shift in consumer behavior as customers sought to avoid higher population density in larger stores, this trend was already noticeable back in 2020, where discount stores accounted for the largest share of grocery revenues in the country.

Fourthly, the increasing ethnocentrism in terms of food is changing the competitive landscape of grocery retailing in Poland. Historically, brands such as Tesco and Carrefour were key players in the retail landscape, accounting for close to 20% (estimated) of the market share combined in 2005. However, in less than 20 years, both Tesco and Carrefour have exited the Polish market due to increasing competition and shifts in customer preferences. According to a consumer survey, ethnocentrism attitudes, particularly regarding food products, are driven by the belief that regional and local products are of higher quality and safety. This belief is expressed by the majority of the population, with close to 80% of respondents holding this view. Therefore, businesses have to adapt by establishing more "local farm-to-table" supply chains and reducing the usage of preservatives to meet this change in consumer taste and preference.

Lastly, on a more recent trend, the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war have exacerbated inflationary pressures. As a result, as much as 73% of consumers now prioritize price over food quality, whereas food quality previously dominated customer preferences.

With these factors in mind, I believe this context will help us understand the value proposition of Dino Polska and explain the trends and prospects moving forward. With that, let's delve into the details of Dino Polska.

Brief history and introduction to Dino Polska

Dino Polska is a Polish grocery retailing company that was founded in 1999 by its founder, Tomasz Biernacki. Dino initially began its operations in western Poland but has since expanded eastwards and now operates 2,340 stores across Poland as of September 30, 2023. Dino defines itself as a "proximity supermarket," representing a new type of grocery retailer that places a strong emphasis on providing a comprehensive range of products at locations conveniently situated close to its customers. This strategic positioning has been adopted by the management since 2015. The former CEO, Szymon Piduch, articulated Dino's positioning in the retail landscape with the following statement:

“The government’s Family 500+ program and the steady increase in minimum wages promote individual consumption in Poland. This is particularly noticeable in smaller towns where Dino stores are located. We operate on the promising segment of proximity supermarkets, which according to market forecasts will be the fastest-growing retail food segment in Poland in 2015–2020 in terms of the average annual increase in the number of stores.

The fast lifestyle connected with longer and longer worker hours is a major factor shaping shopping habits. Customers want to buy grocery products at locations that are nearby and convenient to them, shopping even several times a week. Meanwhile, consumer awareness in health is growing, which also contributes to the great interest in fresh, local products, perceived as healthier. The proximity supermarket segment meets customers’ changing preferences, combining a location convenient for the customer with a wide assortment, and high quality at price competitive prices.”

- Ex-CEO Szymon Piduch comments on the prognosis for the retail market and proximity segment

According to the company's website, Dino initiated its expansion efforts in 2010 by seeking external capital of 200 million zloty from the private equity firm Enterprise Investors, in exchange for a 49% stake in Dino. Subsequently, in 2017, Dino conducted an initial public offering (IPO) and became listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange at a price of 34.5 zloty per share. Notably, there was no mention of equity issuance in the statements, which suggests that this move was likely an exit strategy for Enterprise Investors. Since then, Dino has accelerated its growth significantly, going from 110 stores in 2010 to a current count of 2,340 stores. The rate of store openings shows no signs of slowing down, as Dino continues to open nearly one store every day of the year. An investment of $1,000 in Dino would have grown to $70,000 today, representing a remarkable 70x compounding return.

Management and Board of Directors Analysis.

This is undoubtedly one of the more complex aspects of the analysis, partly due to the somewhat intricate corporate structure of Dino Polska. Dino was led by CEO Szymon Piduch, who joined Dino back in 2002 and initially held responsibilities for the group's finances. In 2010, he assumed the role of President of the Board and was primarily in charge of expansion, investments, and shop operations. However, in 2020, Szymon Piduch suddenly resigned from the management role and was transitioned to the board as a supervisory member. The following year, he resigned from the board altogether, leaving a gap in the CEO position that wasn't promptly filled by a specific individual.

On the company's website, the executive team includes COO Izabela Biadała, responsible for store operations, procurement, sales, administration, and other corporate functions; CFO Michał Krauze, overseeing finance, expansion, and internal risk management; and Director of the Control Department, Piotr Ścigała, who organizes and supervises the operations of stores and distribution centers. No CEO was elected to take over Szymon Piduch's role. However, based on my own speculation, it appears that Dino is in no hurry to find a CEO, possibly because the majority shareholder and founder, Tomasz Biernacki, seems to be actively involved in steering the company.

Tomasz Biernacki is a fascinating figure to learn about. According to Bloomberg, he is known for his frugality and reclusive nature. He often declines media interviews and hasn't granted any major interviews since his Ferrari F430 accident in 2008. It's noteworthy that he didn't appear during his company's initial public offering (IPO) in 2017, and it's said to be rather challenging to get in touch with the management. Interestingly, according to the prospectus, Tomasz is also the owner of several other companies, including ATB Gaming, which owns an e-sports team of the same name, the PH DAVI cosmetic wholesale chain, IT company Itecom, and Browar Krotoszyn. The finance newspaper, money.pl, notes that he once ran a disco bar in Krotoszyn. Despite Dino's emphasis on a super-local philosophy, Tomasz Biernacki is not known for being actively involved in the local community. The current mayor of Krotoszyn, Franciszek Marszałek, mentioned that he has met Tomasz only once, even though they both live in the same city. Most people describe Tomasz as a reserved individual who has made a deliberate choice to avoid the media. Nevertheless, there are rumors circulating about Tomasz purchasing a palace near a village and traveling solely by helicopters, adding interesting anecdotes to the image of the person who might be leading Dino Polska behind the scenes.

Industry Trends and Changes

Source: Roland Berger analysis based on PMR, EMIS, Euromonitor, company webpages and expert interviews

Over the past 15 years, Poland’s organized grocery retailing sector has experienced a pronounced shift from traditional “Mom & Pop” stores to modern retail formats such as the discount stores, supermarkets, and hypermarkets. As shown in the analysis conducted by Roland Berger, modern retailers increased their market share from 65% in 2010 to 80% in 2015, a 3 % shift in spendings annually. As previously mentioned in my analysis on BIMAS in Turkey, reasons for the shift towards modern retailers are often attributed to structural factors such as “heightened hygiene standards, enhanced convenience, superior comfort, and an amalgamation of quality and pricing advantages.”.

Looking deeper into the retail mix within the modern retailers, we can start to see that the discounters were the biggest beneficiary of the shift from traditional retailers to modern retailers. The market share of discounters stood at 15% in 2010 but increased to 26% in less than 5 years. Furthermore, according to a recent report by Euromonitor, this market share of discounters has increased to 35% in 2022 and is projected to increase to 41% by 2027.

Now, if we were to look at the chart above, we would think that the industry positioning that Dino is participating in, namely proximity supermarkets, does not seem to be the main beneficiary of this increased spends in discounters. While this is true that the future growth in Poland is likely to remain in the discounter segment, what is so unique about Dino is the fact that it is both a proximity supermarket and a discounter, as Dino practices a pricing policy where it benchmarks it prices to “discounter” grocery chains. Therefore, by extension, the same tailwinds that discounters will experience, also will apply to Dino.

This brings me to my last point on the industry trend and changes- there may be a fundamental shift in customer behaviour and preference of which the current discounters do not address the gap. This change in behaviour and preference is the preference for convenience and proximity (preferably within walking distance) as well as the option for fresh foods and in particularly, fresh meats. Dino is currently the only “discounter” which offers fresh meats as compared to the rest of the competitors who namely offers packaged meats.

But when thinking about the sustainable appeal of Dino, one needs to ask “Is fresh meats really a compelling and strong enough offering to keep consumers coming back to our stores for the next 10, 20 years? What if competitors too start offering fresh meats?” Well, when thinking for this perspective, perhaps Dino is not a laggard, but an industry leader by being able to offer lowest prices, full-fledge product SKUs and fresh meats, but yet, outperforms closest competitor on a EBIT basis by 2 times. This is driven by the fact that Dino Polska is a vertically integrated provider, with fast inventory turn due to their ability to offer fresh meats as well as their location by being close to their customers.

Store Location Analysis

In my attempt to map out the stores of Biedronka and Dino Polska in Poland to understand store concentration, placement, and "white spaces" and to verify the respective companies’ strategies and views on the rural opportunities in Poland, I observed several key insights.

At first glance, there's a noticeable contrast in store concentration between Biedronka and Dino Polska. Biedronka displays clusters of stores mainly in urbanized regions, especially in the south of Poland (Krakow/Katowice) and the central part of Poland (Warsaw). On the other hand, Dino Polska's store concentration is less distinct, with a greater focus on urban areas compared to Biedronka but still significantly less concentrated. The fact that Dino Polska has never closed a store, combined with the high LFL sales in its stores and the management's emphasis on a lower catchment area, aligns with what I had previously heard about the company's strategy.

I came across some considerations and opinions posted on SeekingAlpha by a reader named Martin McFly (link: https://seekingalpha.com/symbol/DNOPY). He points out that LFL (like-for-like) sales are closely linked to inflation, and the savings of Poles are nearly depleted. Moreover, the management mentioned in Q2 that they are unlikely to raise prices further. The Polish government introduced an anti-inflation shield in 2022, reducing VAT on food items, and this policy is set to end this year. Consequently, this could exert additional pressure on suppliers.

I agree with Martin McFly on this point. If there is a structural reduction in purchasing power, it would indeed pose a headwind for companies across Poland, affecting not only Dino Polska but also companies like Biedronka. Furthermore, Dino's positioning as both a proximity supermarket and a discounter, benchmarking its prices weekly against national discounters, positions it well to benefit from consumers potentially trading down.

Lastly, let's consider the value proposition of the proximity supermarket segment as a whole. It essentially says, "Instead of driving to a distant supermarket, come to us and enjoy a short walk, as we're usually located around 20 to 25 minutes walking distance from you." I believe this seemingly small point is actually crucial. Consumers weigh the cost of traveling to more distant stores for similarly priced items. Instead, they can walk to their nearby Dino Polska store and access a comprehensive product offering (about twice as wide as its discounter counterparts) along with a fresh meat selection in each store. This perspective has given me a better understanding of Dino Polska's value proposition.

Furthermore, Martin McFly also noted that the eastern and southern regions of Poland have higher purchasing power due to Germans and Czechs making purchases there. In contrast, eastern Poland has considerably lower purchasing power. This observation is intriguing, and it makes me wonder about its impact on both Dino and Biedronka, considering their strong presence in these areas. When it comes to grocery spending, I believe that the variation between the daily food necessities of white and blue-collar individuals should not differ significantly, as such products are generally considered inelastic. However, the key point to note is that one should not expect the same level of store concentration in the eastern part of Poland, which would affect how we estimate the "total addressable market" (TAM) of stores for Dino Polska.

Key Moat

This brings me to the key business analysis of Dino and what I believe is the key moat of Dino.

Subsidiaries of Dino Polska

I believe that the primary moat of Dino Polska lies in its vertical integration for key product offerings. As highlighted earlier, Dino owns two subsidiaries: Agro-Rydzyna, a company that processes meats, and Dino Krotosynz, which processes and preserves meats for sale. I've previously discussed the significance of meat in a typical Pole's diet, and the value of offering fresh meats in stores conveniently located for customers. However, running and operating a meat processing business is a complex endeavor. It requires an in-depth understanding of how to efficiently utilize the processing plant and a keen insight into consumer demand and supply dynamics.

According to independent analyst Aure's notes (link: https://auresnotes.com/tomasz-biernacki.), it appears that the Biernacki family has deep-rooted experience in the meat production industry. They started with a small slaughterhouse in 1993, expanded into regional beef and pork production, and in 1998, built a meat storage facility with a capacity of 25,000 tons. The family further expanded by constructing a brand-new slaughterhouse in 2022, one of the largest in Poland.

Considering that running a meat processing operation is a challenging business that requires expertise in plant management and a deep understanding of consumer demand and supply, it brings me a degree of comfort to know that Dino Polska possesses this advantage, setting it apart from its competitors. Vertical integration also means that Dino Polska may have an information edge in its meat sales. I estimate that meat sales account for more than 20-30% of its revenue, given that the average Polish diet consists of a minimum of 15% daily protein intake (on average). Additionally, proteins are typically more expensive than other food categories.

This information edge suggests that Dino Polska is better equipped to anticipate fluctuations in demand and adjust its plant operations to minimize wastage and discounts. As a result, the company can maintain stable margins while benefiting from higher-margin meat sales. For context, JBS, Brazil's largest meat producer, typically reports average EBIT margins of 7-10%.

Related Party Transaction of Dino Polska

The second point I'd like to discuss regarding vertical integration pertains to an entity called "Krot Invest." I have to admit that I came across this idea in a paper by Sohra Peak Capital on Dino Polska, where they note that Krot Invest is "dedicated solely to the construction of Dino stores." This approach allows Mr. Biernacki and Dino Polska to enjoy several advantages, such as expediting the construction process, eliminating negotiation friction with external construction companies, reducing the likelihood of lawsuits brought by injured third-party construction workers, and ensuring that new stores seamlessly follow the standard Dino store 400 m2 blueprint (Sohra Peak Capital. Link: https://bf9436d9-3e06-4e22-bbf4-9c87456898e3.usrfiles.com/ugd/bf9436_528d4abacc484d2c92ca22ad9facd215.pdf).

According to their estimates, about 95% of Dino stores are owned, with only 5% being rented. This stands in stark contrast to its competitors, who primarily lease their stores. This scenario reminds me of a parallel with an exceptional company, Copart Inc, whose key moat lies in the fact that it owns the lands of junkyards compared to its competitors who mainly lease. Owning the land, or in this case, the stores, offers significant advantages. Dino insulates itself against rental inflation and, more importantly, gains the flexibility to strategically choose store locations that optimize the highest traffic flow within the low-store catchment area it operates within.

The ability and flexibility to choose store locations based on the highest traffic flow/density per square meter is an advantage that neither Biedronka (Jeronimo Martins), Tesco, Carrefour, Eurocash, nor others does not have the liberty to do so; They are constrained by the availability of rental locations. I believe that the choice of a suboptimal rental location has significant long-term effects, and in my opinion other entrants and players rather than Jeronimo Martins. The latter had the advantage of being the first mover and leasing out better locations in both rural and urban regions.

However, the downside of building and owning stores is that it's a capital-intensive approach. This is evident as the free cash flow margin for Dino Polska over the past three years has been negative, ranging from approximately -1.5% to -4%, relative to its peer Jeronimo Martins, which generates an average free cash flow margin of 3.5% to 4.5%.

Nonetheless, when we look at metrics like return on assets and return on capital, Dino Polska demonstrates strong performance. It averages a return of 10-12% on assets, while Jeronimo Martins averages 4-5%. For return on capital, Dino Polska averages a return of 16-18%, while Jeronimo Martins averages 8-12%. Therefore, the focus should not be solely on free cash flow generation, but rather on how productive the assets are. If employing a capital-intensive asset approach allows Dino Polska to position itself strategically for long-term, structural consumer trends and maintain higher competitive margins, I believe that the trade-off of lower free cash flow generation in the near term is an approach worth encouraging before competitors employ similar tactics.

TAM Assessment

The key driver for any retail sales is driven by either growth in the number of stores or growth in the average spends of a consumer, either through higher frequency of visits or higher average spends per basket. Therefore, having an idea of the potential high-water mark of the number of stores allow us to understand just how much more growth there is.

For Dino, the number of stores has grown at an impressive pace, from 111 stores in 2010 to 2156 stores in 2022. Management has guided open stores at a rate of one at least 1 per day. In 2023, it has opened about 184 in the 1H of the year, expecting the total ending store to be around 2,564 stores for FY2023. But this is not important given that currently, Dino Polska only has around 2,564 stores, and about 6% of retail sales. Its competitor, Jeronimo Martins, has about 3,400 stores across Poland and accounts for about and is expected to open about 130 -150 stores in FY2023. Of course, Jeronimo Martins would argue that there is still significant runway for store count growth, but my scepticism would estimate the cap at around 5,000 to 6,000 stores, justified by a sense of gut-feeling and accurate guestimation.

But a closer rough estimation on a macro top-down approach, using Dino’s headquarters Krotosynz as an example of a visualization of what a mature store and city look like, we start to be able to estimate the highest number of potential stores.

I have credited Sohra Peak Capital’s estimation below. I have mainly adjusted it to better reflect changes in purchasing power between east and west Poland and updated the numbers.

Based on the top-down approach of TAM estimation, we get to see that the upper limit for the number of stores Dino can potentially be about 7,000 to 8,000.

Now, the third way to think about this TAM is through rough estimation using quick demographics. Poland has about 38 million in population. Turkey has about 2.3x more population, at around 84 million. Turkey currently has about 20k discounters, but the end-steady state is more towards 30k-40k number of stores, as the shift towards modern retailing only stands at 60% market share for modern retailers as compared to Poland’s 80%. If we just assume an equal ratio for Poland, this places the store count to be towards 15k – 20k stores for maximum saturation. This seems reasonable high-water mark and is in line with our 2 other approaches.

Store economics

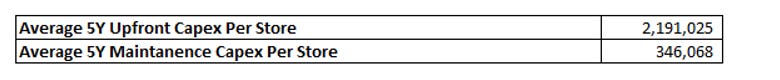

As mentioned above, Dino Polska constructions its own stores and therefore, I am curious about the store economics and the return on invested capital based on a single-store economics. I have included a screenshot of how I managed to calculate the average 5Y upfront Capex per store and Maintenance capex per store in the appendix.

The key insight here is that it will first, cost about 3mil upfront capex (I have adjusted it higher due the the trend of higher upfront costs in recent years) while maintenance capex per store is around 350k per year. Note that, Dino Polska capital intensity will decline overtime, while maintenance capex becomes the largest component of capital expenditure over time. Based on my model, this happens in FY2031E as new store expansion decline and FCF conversion stabilizes at around 78 – 80% of Net Income.

Economics of Store

I guess the key question after modelling this out is figuring out, whether if owning the store, besides the qualitative advantages that I talked about above, has an economic validity to it. Afterall, if owning the store does not make economic sense, then perhaps Dino competitors are making the right decision.

According to a real estate article that promotes investments in buildings for leasing to Biedronka, renters can expect an monthly rental income of 30,000 – 120,000 PLN, depending on location and store size. If we take an average of 75,000 PLN monthly * 12 = this equates to about 1 million PLN in a year. This rough estimation means that when comparing it to Dino store economics, Dino will only need to ensure that it stores will do well for at least 3 years. If Dino shuts down any stores within the first 3 years, then the economics of this approach will not make any sense. As I checked the history of Dino store closures over the past 10 years, Dino has not yet closed any stores. Therefore, this seems to give me some comfort that approaching this capital-intensive model, though may seem counterintuitive, may be the correct move given the economics and the qualitative advantages that it brings.

Valuation

Finally, is Dino a good buy? Well, based on my assumptions which I believe are to be reasonable, Dino appears to be at fair value given current market capitalization. On a multiple basis, Dino appears to be only cheap around FY2026 to FY2027. My personal style has always been to buy companies that are both quality and contains a significant margin of safety. Therefore, Dino does not quite cut it yet for me. I would be looking to buy the company should the company misses on a year of results and when the share price corrected. Nonetheless, this is a great company to keep on one’s watchlist. I have included my model and assumptions below in the appendix.

Model

· Note that LFL sales is driven by inflation in recent years. My LFL growth is mainly assuming its stores will grow better than inflation.

· For store growth, if we look at the # of stores per 100k population as well as the catchment area, this has yet to reach the mature catchment area of Krotosynz of around 3,000 people per store, therefore, I believe it to be not yet testing the limits of the store economics.

· Margin continues to improve driven by recovery of gross profit margins due to larger number of store build outs. Historically, GP has reached around close to 26%. I am only suggesting a reversion back to the level of 25%, representing a structural uplift of 1% which I believe seems to be reasonable given that the number of stores would have close to tripled.

Appendix

References

McKinsey Report:

Title: How Poland can become a European growth engine

URL: McKinsey Report

Flanders Investment and Trade Market Study:

Title: The Biggest Retail Chains In Poland 2020

Statista - Poland Biedronka Store Network:

Title: Poland Biedronka Store Network

Statista - Poland Food Expenditure:

Title: Poland Food Expenditure

Local File - Grocery Retail in Poland 2010-2020:

Title: Grocery Retail in Poland 2010-2020: Detailed Analysis of Convenience and Proximity Supermarkets

Local File - Small Towns and Rural Areas:

Title: Small Towns and Rural Areas as A Prospective Pla

Manager Money - Tomasz Biernacki:

Title: Kim jest właściciel Dino Tomasz Biernacki

NDTV - Tomasz Biernacki:

Title: Tomasz Biernacki: Dino Polska SA, Reclusive Billionaire Thrives as Pandemic Shoppers Crowd His Stores

BMC Public Health Article:

URL: URL

Sohra Peak Capital

URL: URL

Dino Polska Strategy:

Title: Strategy

Dino Polska History:

Title: The History

Dino Polska IPO Announcement:

Title: Dino Polska Publishes Prospectus and Launches Initial Public Offering

Statista - Poland Number of Stores Per Channel:

Title: Poland - Number of Stores Per Channel

Statista - Poland Retail Stores by Format:

Title: Poland - Retail Stores by Format

Poland Statistical Office - Internal Market in 2018:

Title: Internal Market in 2018

USDA Retail Foods Guide 2022:

Title: Retail Foods Guide - Warsaw, Poland

USDA Poland Retail Sector Report 2019:

Title: Poland Retail Sector - Warsaw, Poland

USDA Poland Exporter Guide:

Title: Poland Exporter Guide

USDA Retail Sector Report 2018:

Title: Poland Retail Sector - Warsaw, Poland

USDA Retail Foods Sector Report 2016:

Title: Retail Foods Sector - Warsaw, Poland

USDA Poland Retail Sector Report 2019:

Title: Poland Retail Sector - Warsaw, Poland

PubMed Central Article: Analysis of Consumer Behaviour in the Context of the Place of Purchasing Food Products with Particular Emphasis on Local Products

Title: Analysis of Consumer Behaviour in the Context of the Place of Purchasing Food Products with Particular Emphasis on Local Products

URL: URL

Dino Polska 2022 Consolidated Financial Statements:

Title: Dino Polska Group 2022 Consolidated Financial Statements

Dino Polska 2022 Audit Report:

Title: Dino Polska Group 2022 Audit Report

MDM - MBank Dino Research Paper

Title: MBank Dino Research Paper

URL: URL